A little background on the silver issue, as well as its associated economic population dislocation associated with it, during the final 80 years of Ming might be apropos:

Silver has traditionally been in short supply across the sinosphere since the Tang dynasty, when the major silver mines in the sinosphere were exhausted. so the amount of silver that circulated in east Asia has been steadily dwindling due to loss and wastage since the beginning of Song. The introduction of paper currency by the Song dynasty was done to combat the powerful deflationary effect s of dwindling silver reserve.

It is estimated at the Beginning of Ming dynasty, there were at most a few tons of silver remaining in circulation in east asia to back up the system of paper currency instituted during Song and perpetuated under Yuan.

During the Ming dynasty, for controversial reasons counterfeit control completely collapsed and paper money counterfeiting ballooned . As a result paper money were withdrawn from circulation and precious metal economy returned. But the problem of diminishing amount of silver available was not solved. So silver was increasingly replaced by copper as the main medium of exchange for most transactions throughout the economy. Silver itself became high status high value exchange medium.

Then in the 1550s the long term decline in the role of silver to that of copper reversed. During the early 1500s, China came into contact with the Spanish through the Philippines. Shortly afterwards the Spanish discovered the Potosi silver mine in Peru. This was and remains by far the largest and richest silver mine ever discovered. Silver mined from Potosi continues to makes up more than half of all the silver specie in circulation around the world. The Spanish quickly exploited the astonishing wind fall, the Chinese thirst for silver, and the long-standing European thirst for Chinese luxury goods, by establishing a circumglobal trade where conquistadors go west from Europe to Peru, where they emslave Indian labors to extract silver cheaply and with enormous loss of life. The silver is the. cast into ingots and transshipped west through Philippine to China, where they are exchanged for Chinese silk and porcelain, which are then shipped west to Europe, completing the circumglobal trade and sold for a large profit.

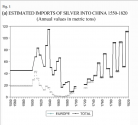

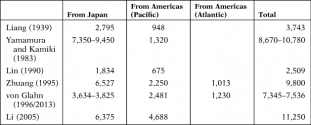

So between 1550 and 1630, it is estimated more than 10,000 tons (about 250 million Chinese teals) of Potosi silver were exported to china in exchange for Chinese silk and porcelain merchants. This tripled the silver in circulation in China, and made it possible for silver to be again the preeminent medium of exchange in the Chinese monetary system.

The inflow of so much silver in a relatively short time totally transformed the agriculture landscape in much of the coastal china. Large tracts of prime agricultural land were withdrawn from food production by large land owners and devoted to mulberry tree raising to feed the silkworms to make more silk because it is so much more profitable to exchange silk for silver than rice or millet for copper. Large areas of forested land were similarly denuded of trees to feed porcelain kilns. Large number of peasants who couldn’t adapt from rice and millet production to Mulberry tree growing were driven off of their traditional farm lands and forced the migrate inland where they started to plant corn and potatoes, both also Spanish American imports, on hitherto uncultivatable uplands. By 1610 much of Chinese south East coastal went from subsistence agricultural economy to focus on luxury goods production. Farther inland hitherto marginal uplands that have been protected by natural forest are now devoted to corn and potato growing by migrant farmers forces off their land at the coast. Potato and corn have negligible soil protection value. The soil lost through erosion washes down hill onto river flood plains where traditional river valley based farming that has been the core of Chinese arbor culture for thousands of years primarily occurred. So this impoverished the local farmer as well. So the net effect is the tremendous influx of silver and wealth into China thanks to the Spanish trade was calamitous to a large part of Chinese peasantry. Even worse than the dislocation, Chinese peasants have no access to the silver because the silver came from abroad through merchants and crafts class, who didn;t depend very much on the food producing peasants. But the dominance of silver based trade to the Chinese economy means land rents are also demanded in silver. This is a double Whammy for the peasantry in a large part of China.

The net effect is, while the total wealth in Chinese society greatly increased during period, the peasantry experienced tremendous dislocation and impoverishment.

At the same time, the luxury goods production in coastal China became, in modern parlance, highly leveraged. In anticipation of ever higher inflow of Spanish silver year after year, the silk and porcelain merchants borrowed heavily against next years’ s expected earnings to invest in additional mulberry trees and porcelain kilns. If the flow of silver stopped, there will be financial ruination.

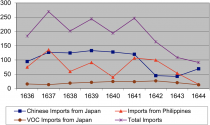

In 1630, the flood of silver into China went into precipitous decline. This was caused by another calamitous event, this time in Italy. In Europe this was the middle of the 30 year war. The Hapsburg monarch was neck deep in the war. Mercenaries hired by the Hapsburg monarchy marched through northern italy and spread a plague that killed a quarter of Italian population in one year. Northern Italy at the time was still the richest part of Europe, and thus the richest part of Hapsburg holdings. The Hapsburgs were hurting. Their distress did not go unnoticed. The war against the Hapsburgs turned decisively more vicious during the plague.

The Hapsburg empire has several parts and the other major part was Spain. In response to the financial ruin in Italy and the bitter turn of the war, the Hapsburgs halted the flow of Potosi silver to China, and ordered it shipped straight to Spain to fill in the financial hole and sustain its war effort.

The result of this is Chinese economy suffered massive inflation that in ten years quadrupled the value of silver, starved millions of peasants, and kindled the Li Zicheng’s uprising that toppled the Ming dynasty then ruling China 14 years later.

Silver has traditionally been in short supply across the sinosphere since the Tang dynasty, when the major silver mines in the sinosphere were exhausted. so the amount of silver that circulated in east Asia has been steadily dwindling due to loss and wastage since the beginning of Song. The introduction of paper currency by the Song dynasty was done to combat the powerful deflationary effect s of dwindling silver reserve.

It is estimated at the Beginning of Ming dynasty, there were at most a few tons of silver remaining in circulation in east asia to back up the system of paper currency instituted during Song and perpetuated under Yuan.

During the Ming dynasty, for controversial reasons counterfeit control completely collapsed and paper money counterfeiting ballooned . As a result paper money were withdrawn from circulation and precious metal economy returned. But the problem of diminishing amount of silver available was not solved. So silver was increasingly replaced by copper as the main medium of exchange for most transactions throughout the economy. Silver itself became high status high value exchange medium.

Then in the 1550s the long term decline in the role of silver to that of copper reversed. During the early 1500s, China came into contact with the Spanish through the Philippines. Shortly afterwards the Spanish discovered the Potosi silver mine in Peru. This was and remains by far the largest and richest silver mine ever discovered. Silver mined from Potosi continues to makes up more than half of all the silver specie in circulation around the world. The Spanish quickly exploited the astonishing wind fall, the Chinese thirst for silver, and the long-standing European thirst for Chinese luxury goods, by establishing a circumglobal trade where conquistadors go west from Europe to Peru, where they emslave Indian labors to extract silver cheaply and with enormous loss of life. The silver is the. cast into ingots and transshipped west through Philippine to China, where they are exchanged for Chinese silk and porcelain, which are then shipped west to Europe, completing the circumglobal trade and sold for a large profit.

So between 1550 and 1630, it is estimated more than 10,000 tons (about 250 million Chinese teals) of Potosi silver were exported to china in exchange for Chinese silk and porcelain merchants. This tripled the silver in circulation in China, and made it possible for silver to be again the preeminent medium of exchange in the Chinese monetary system.

The inflow of so much silver in a relatively short time totally transformed the agriculture landscape in much of the coastal china. Large tracts of prime agricultural land were withdrawn from food production by large land owners and devoted to mulberry tree raising to feed the silkworms to make more silk because it is so much more profitable to exchange silk for silver than rice or millet for copper. Large areas of forested land were similarly denuded of trees to feed porcelain kilns. Large number of peasants who couldn’t adapt from rice and millet production to Mulberry tree growing were driven off of their traditional farm lands and forced the migrate inland where they started to plant corn and potatoes, both also Spanish American imports, on hitherto uncultivatable uplands. By 1610 much of Chinese south East coastal went from subsistence agricultural economy to focus on luxury goods production. Farther inland hitherto marginal uplands that have been protected by natural forest are now devoted to corn and potato growing by migrant farmers forces off their land at the coast. Potato and corn have negligible soil protection value. The soil lost through erosion washes down hill onto river flood plains where traditional river valley based farming that has been the core of Chinese arbor culture for thousands of years primarily occurred. So this impoverished the local farmer as well. So the net effect is the tremendous influx of silver and wealth into China thanks to the Spanish trade was calamitous to a large part of Chinese peasantry. Even worse than the dislocation, Chinese peasants have no access to the silver because the silver came from abroad through merchants and crafts class, who didn;t depend very much on the food producing peasants. But the dominance of silver based trade to the Chinese economy means land rents are also demanded in silver. This is a double Whammy for the peasantry in a large part of China.

The net effect is, while the total wealth in Chinese society greatly increased during period, the peasantry experienced tremendous dislocation and impoverishment.

At the same time, the luxury goods production in coastal China became, in modern parlance, highly leveraged. In anticipation of ever higher inflow of Spanish silver year after year, the silk and porcelain merchants borrowed heavily against next years’ s expected earnings to invest in additional mulberry trees and porcelain kilns. If the flow of silver stopped, there will be financial ruination.

In 1630, the flood of silver into China went into precipitous decline. This was caused by another calamitous event, this time in Italy. In Europe this was the middle of the 30 year war. The Hapsburg monarch was neck deep in the war. Mercenaries hired by the Hapsburg monarchy marched through northern italy and spread a plague that killed a quarter of Italian population in one year. Northern Italy at the time was still the richest part of Europe, and thus the richest part of Hapsburg holdings. The Hapsburgs were hurting. Their distress did not go unnoticed. The war against the Hapsburgs turned decisively more vicious during the plague.

The Hapsburg empire has several parts and the other major part was Spain. In response to the financial ruin in Italy and the bitter turn of the war, the Hapsburgs halted the flow of Potosi silver to China, and ordered it shipped straight to Spain to fill in the financial hole and sustain its war effort.

The result of this is Chinese economy suffered massive inflation that in ten years quadrupled the value of silver, starved millions of peasants, and kindled the Li Zicheng’s uprising that toppled the Ming dynasty then ruling China 14 years later.

Last edited: