I don't want to bring up the debate about deflation, how much is there and what caused it in China. I assumed this was posted before, I'm just checking that our member @doggydogdo isn't the author of this article right?

Last edited:

A growth of 5% per year is quite impressive. 5% per year from 2022, when the consequences of the Covid lockdown began to be overcome, is very difficult for China: it is a race for survival with the US (+2.8% for 2024) and the EU market (+0.8% for 2024) - the most important thing in this race is to prove to investors and the population (also investors) that, despite all the disadvantages, the Chinese economy is growing two to three times faster than its main competitors.Premier Li Qiang delivered the 2025 government work report today, setting the GDP growth target at 5% for this year. The government will also begin to gradually implement free preschool education.

Big if true.Premier Li Qiang delivered the 2025 government work report today, setting the GDP growth target at 5% for this year. The government will also begin to gradually implement free preschool education.

The reporter gathers all the correct facts and, in the end, reaches the wrong conclusion.Japan Learns to Live with Deflation

Ben Bernanke has been lecturing on deflation's perils since he joined the Federal Reserve in 2002 and has often held up Japan as Exhibit A. When the Fed launched QE2, the quantitative easing program to promote credit expansion in the U.S., in November, the central bank chief hoped to avoid the scourge that has devastated Japan's economy. U.S. consumer prices, excluding food and fuel, climbed at their slowest pace since records began in 1959, the Commerce Dept. reported on Dec. 22.

There's something curious about the way the deflation syndrome has played out in Japan, though. The Japanese don't feel that threatened anymore. "Everyone knew deflation was bad for jobs and bad for the economy, but gradually households and companies just got used to it," says Martin Schulz, a senior economist at Tokyo's Fujitsu Research Institute.

Deflation—the steady drop in prices of goods, wages, and services—has many ill effects. Households are stuck paying off mortgages, car loans, and other debt even as their take-home pay has declined. Also, as housing values fall, consumers have smaller nest eggs for retirement. Companies, meanwhile, are unable to raise prices, which puts pressure on profits.

Yet the Japanese have discovered the benefits of deflation as well. Monthly pay dropped to an average 315,294 yen ($3,800) in 2009, the lowest level since the government began tracking wage data in 1990. "It's not like I'm promised any pay raises," says Momoko Noguchi. The 24-year-old Tokyo resident gets by on two part-time jobs by shopping for everything from nail polish to dinner plates at her local 100-yen outlet (the Japanese equivalent of an American dollar store), and she pays 400 yen or less for lunch. "I hope prices keep falling." Four out of five Japanese say higher costs would be "unfavorable," according to a central bank survey.

Faced with consumers such as Noguchi, companies in Japan have actually accelerated deflation. Retailers "have poured a lot of energy into offering products that are cheap but still have high value," says Naozumi Nishimura, an analyst at TIW in Tokyo. "We're seeing some good effects from that."

To help reverse a seven-year decline in same-store sales, McDonald's Holdings Japan, a unit of McDonald's (), introduced a 100-yen menu in 2005. The chain's 100-yen hamburger sold for 210 yen in 1990. "We wanted our customers to know that we've changed," says Kazuyuki Hagiwara, Tokyo-based senior marketing manager at the company. Since the debut of the lower-priced menu, same-store sales have climbed every year. McDonald's Japan shares have returned 17 percent in the past three years.

Price cutting by companies has helped Japanese consumers adjust to deflation. The average household owns 1.4 cars and 2.4 color TVs, about a quarter more than in 1990, a Cabinet Office survey shows. Deflation has helped home buyers, too, by forcing prices down from their peaks in 1990: According to calculations based on yearly Land Ministry data, Japan's residential land prices have dropped by an average of 2.9 percent a year over the past two decades.

Golfers pay 26,800 yen ($324) to play on the weekend with a caddy at the Bobby Jones Jr.-designed Oak Hills Country Club, 90 minutes' drive from central Tokyo. Twenty years ago the fee was about 40,000 yen, says Katsutoshi Ohira, acting manager. All told, the proportion of people content with their standard of living was 63.9 percent last year, compared with 63.1 percent in 1989, a government report said.

Deflation is so entrenched in Japan that companies are exporting it. Fast Retailing plans to open 44 Uniqlo stores overseas this fiscal year. Supermarket chain Aeon has earmarked about $2.5 billion over three years to open stores in China and Southeast Asia. Daiso Industries, which dominates the 100-yen retail sector, now has outlets in more than 20 countries.

In Japan, where 23 percent of the population is over 65, a sudden rebound in prices would hurt pensioners and retirees especially hard. "It's amazing what you can buy with 100 yen now. We didn't have 100-yen stores before," says Sachiko Enokida, 80, who lives on her bimonthly pension checks from the government. "I would hate for things to get expensive again."

So is deflation a blessing in disguise? Not to analysts such as Richard Jerram, head of Asian economics at Macquarie Securities (). He points out that as businesses cut prices to compete, it becomes harder to borrow and invest. "It's extremely corrosive," he says. Deflation, adds Jerram, will steadily sap Japan's nominal growth and deprive the government of tax revenue. Eventually, Japan may no longer be able to finance its borrowing. The country will then either have to default on debt that's about twice the size of the economy or devalue its currency to reduce the real value of liabilities. "That's the unavoidable endgame," says Jerram, who has analyzed the Japanese economy since 1987. "As long as it's in the future, everybody can pretend it's someone else's problem."

The bottom line: Although deflation ultimately poses a serious threat to Japan, ordinary consumers are benefiting from lower prices.

falling price is the market's way to show, people can make new shit cheaper than beforeIt's funny this desperate search to talk about deflation. Although everything they say deflation does to the economy as a negative consequence, this in no way changes the benefits of deflation.

It is the country that lived with deflation:

The reporter gathers all the correct facts and, in the end, reaches the wrong conclusion.

Worse than the shocking discovery that consumers like to see prices falling (who would have thought that?!), is the twisted reasoning of that economist in the penultimate paragraph who said that price deflation is "corrosive" and would bring disaster to the Japanese economy.

First of all, all of Japan's problems do not come from price deflation, but from the government's ignorant fiscal policy, which in a foolish and futile attempt to combat price deflation, went around spending on useless things, destroying savings and indebting the country to the pornographic level of 200% of GDP.

If it had not done this, the price deflation scenario would continue, but with one considerable difference: the economy would be based on a mountain of capital and not on a mountain of debt.

This fiscal policy was undoubtedly one of the main causes of Japan's low economic growth -- for a people who save a lot, one would expect more robust annual growth rates. However, since the government uses up all these savings to finance its deficits, investments are compromised, since there are no surplus funds to finance them. And this hampers growth.

If the government reduced its spending to the point of eliminating its budget deficit (in nominal terms), it would no longer need to borrow money to close its budget. In other words, it would no longer need to rely on citizens' savings. This would make more funds available to be lent to the private sector, both to businesses and consumers. The savings that the government would have absorbed by selling bonds would now be available to be used more profitably by entrepreneurs and consumers.

Another flaw in the economist's reasoning: if prices are falling for everyone, then, as a matter of logic, they must be falling for the government too. Therefore, it makes no sense to conclude that the government will be deprived of revenue and will not even be able to finance its loans. It just needs to reduce its payroll and cut expenses, to be more efficient.

However, the economist comes to the terrifying conclusion that the government’s difficulty in collecting more taxes will be the real obstacle to Japan’s future economic growth.

Contrary to what traditional economists think, who confuse falling prices with economic recession, the fact is that there is nothing bad about price deflation in and of itself. Quite the contrary: falling prices are the natural result of a growing market economy and prudent money management. If the quantity of products increases, but the money supply remains relatively unchanged, then the natural result will be a fall in prices, to the benefit of savers and consumers. This happened during the second half of the 19th century in the United States, still under the classical gold standard.

Falling prices and rising living standards, both generated by higher productivity, are exactly the two things that every economy should strive for. Japan – mainly due to the entrepreneurial and disciplined culture of its people – had great potential to achieve this arrangement in a sustainable way. But it will not succeed precisely because of its government, which, following the advice of Keynesian economists, has become deeply indebted and, as a result, has been sucking up a large part of the economy's capital, which inhibits more productive investments.

As the report showed quite inadvertently, Japanese families and companies have adapted to the environment of price deflation. Contrary to theory, both thrive in this scenario.

Price deflation and a higher standard of living are completely interconnected factors, and the former should never be condemned by sensible people.

There is nothing "corrosive" about deflation, as the economist said. But there is everything corrosive about a government that spends, goes into debt and leaves a country's economy with a debt that is simply twice the size of its GDP.

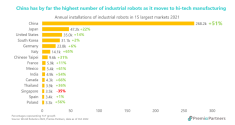

Abundance and a significant increase in productivity. For example China still buy oil and gas from Iran and Russia, that gives China an abundance of cheap energy, from Russia and even Ukraine they get cheap food, despite having a massive domestic agricultural production. China is also leading the world in automation which has lead to a massive increase in productivity.

I don't want to bring up the debate about deflation, how much is there and what caused it in China. I assumed this was posted before, I'm just checking that our member @doggydogdo isn't the author of this article right?

I don't want to bring up the debate about deflation, how much is there and what caused it in China. I assumed this was posted before, I'm just checking that our member @doggydogdo isn't the author of this article right?

It's funny this desperate search to talk about deflation. Although everything they say deflation does to the economy as a negative consequence, this in no way changes the benefits of deflation.

It is the country that lived with deflation:

The reporter gathers all the correct facts and, in the end, reaches the wrong conclusion.

Worse than the shocking discovery that consumers like to see prices falling (who would have thought that?!), is the twisted reasoning of that economist in the penultimate paragraph who said that price deflation is "corrosive" and would bring disaster to the Japanese economy.

First of all, all of Japan's problems do not come from price deflation, but from the government's ignorant fiscal policy, which in a foolish and futile attempt to combat price deflation, went around spending on useless things, destroying savings and indebting the country to the pornographic level of 200% of GDP.

If it had not done this, the price deflation scenario would continue, but with one considerable difference: the economy would be based on a mountain of capital and not on a mountain of debt.

This fiscal policy was undoubtedly one of the main causes of Japan's low economic growth -- for a people who save a lot, one would expect more robust annual growth rates. However, since the government uses up all these savings to finance its deficits, investments are compromised, since there are no surplus funds to finance them. And this hampers growth.

If the government reduced its spending to the point of eliminating its budget deficit (in nominal terms), it would no longer need to borrow money to close its budget. In other words, it would no longer need to rely on citizens' savings. This would make more funds available to be lent to the private sector, both to businesses and consumers. The savings that the government would have absorbed by selling bonds would now be available to be used more profitably by entrepreneurs and consumers.

Another flaw in the economist's reasoning: if prices are falling for everyone, then, as a matter of logic, they must be falling for the government too. Therefore, it makes no sense to conclude that the government will be deprived of revenue and will not even be able to finance its loans. It just needs to reduce its payroll and cut expenses, to be more efficient.

However, the economist comes to the terrifying conclusion that the government’s difficulty in collecting more taxes will be the real obstacle to Japan’s future economic growth.

Contrary to what traditional economists think, who confuse falling prices with economic recession, the fact is that there is nothing bad about price deflation in and of itself. Quite the contrary: falling prices are the natural result of a growing market economy and prudent money management. If the quantity of products increases, but the money supply remains relatively unchanged, then the natural result will be a fall in prices, to the benefit of savers and consumers. This happened during the second half of the 19th century in the United States, still under the classical gold standard.

Falling prices and rising living standards, both generated by higher productivity, are exactly the two things that every economy should strive for. Japan – mainly due to the entrepreneurial and disciplined culture of its people – had great potential to achieve this arrangement in a sustainable way. But it will not succeed precisely because of its government, which, following the advice of Keynesian economists, has become deeply indebted and, as a result, has been sucking up a large part of the economy's capital, which inhibits more productive investments.

As the report showed quite inadvertently, Japanese families and companies have adapted to the environment of price deflation. Contrary to theory, both thrive in this scenario.

Price deflation and a higher standard of living are completely interconnected factors, and the former should never be condemned by sensible people.

There is nothing "corrosive" about deflation, as the economist said. But there is everything corrosive about a government that spends, goes into debt and leaves a country's economy with a debt that is simply twice the size of its GDP.